Cape Town, January 2, 1968. A sweltering hot midsummer's day. The handsome 45-year-old surgeon’s eyes above the mask did a last, slow, deliberate round of those closest to the table. From each he got an almost imperceptible ready-when-you-are nod. The artist’s hand, already showing signs of the crippling arthritis that was to retire it, checked the balance of the scalpel, hovered a moment above the 58-year-old dying dentist’s chest, and went in. This kindest cut of them all held the promise of a new heart, and a new life.

Not twenty metres away, on a small landing on the stairs, I loitered with intent; intent on getting the first photographs ever taken of a successful heart transplant operation. Some chance! What with 120 of the world’s most experienced and best bankrolled television crews, photographers and journalists milling about Groote Schuur Hospital’s main entrance below me - and several back and side entrances as well. The odds on the local boy were long indeed.

And yet, I was hopeful. All I needed was for Dr. M’s nerve to hold, for the Minox spy camera to function smoothly, and for him to keep his assignation with me on those stairs.

I heard footsteps. It was far too soon! This couldn’t be him. In a cold sweat I glanced about me frantically for a hiding place. The broom cupboard on the landing, yes, that would be my bolthole. As the footsteps approached, I lurched for the cupboard door...

Perhaps, to get all this in perspective, I should give an account of events that had led to this point. This dentist being cleaved, a certain Dr. Philip Blaiberg, was not the first man in the world to receive a heart transplant. The first, 53-year-old Louis Washkansky, a barrel of a man I seem to remember photographing as he refereed wrestling matches, had received his new heart a month before, on December 3, 1967, but lived on for only 18 days. Moreover, no pictures whatsoever had been taken of his operation. Maybe they had not wanted to blow up the whole affair in case it had failed. Maybe they had been pre-occupied with the intricacies of that groundbreaking operation. Or maybe they had not realised just how shattering their actions were to be. For them, it was medical intervention. But for the world’s one billion Catholics, to mention just one group, they were on God’s terrain and messing with man’s soul. This was radical stuff: if the heart was merely a pump, where, then, did the soul reside? Where did one’s love spring from? Where was the centre of our being?

News of that first heart transplant reverberated around the world and made Professor Christiaan Neethling Barnard an instant celebrity. Other surgeons rushed (some would say with indecent haste) to do likewise. Just three days after the first transplant, Adrian Kantrowitz performed the first infant-to-infant transplant - and the first heart transplant in the United States - at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn. Photographs recorded the operation, yet it was not a success. The recipient, an infant boy, succumbed to a bleeding complication six and a half hours later.

But the world’s focus was still firmly on Barnard, the missionary’s son from Beaufort West in the Great Karoo Desert. After all, the world seldom remembers those who come second. The media’s big players had started flying into Cape Town, and when rumour had it Barnard was on the point of performing his second heart transplant, a veritable stampede began. Enough to send the jitters up a 26-year-old photo-journalist who had just turned free-lance - me.

“That’s a story worth watching,” the mother of my two small children had told me. Though we were both third-generation in newspapers, my wife was the one with ink in her veins. Her father, Victor Norton, had been editor of The Cape Times from the age of 32.

And thus I joined the mad scramble. In the early rounds, this meant wheeling and dealing, though as a penniless young father, it was more a case of wheedling for me. Stumbling and bumbling through the giant maze that had arisen overnight, I sought desperately for a way to get into the operating theatre the day the second heart transplant was to take place - whenever that might be.

Rumours abounded, the most plausable being that one of the giant U.S. networks had outbidden everyone and would be given exclusive rights to film right inside the operating theatre. Exclusive for filming, that is. The rumour also had it that one stills photographer would, by royal decree of the King of Hearts himself, be granted entry to the inner sanctum. This fellow, it was said, had introduced the handsome young heart surgeon of legendary libidinousness, to many of his female models.

With as much chance of success as an ant setting out to ravish an elephant, I kept plodding and plodding and plodding... Against all the odds, I struck gold. Or was it fool’s gold? Time would tell. Via many convoluted byways I came upon a member of the transplant team who was bearing a grudge. Dr. Reuben Sougin Mibashan, haematologist and bit-part player in the 30-man/woman team, felt that his department had been short-changed when it came to the allocation of funds, thus impeding his blood research programme. Waving my newly-acquired accreditation for one of the world’s top three wire services - I had carte blanche to transmit whatever pictures I deemed newsworthy - I had the good doctor’s undivided attention.

“Fifty-fifty,” I purred in his ear. “I guesstimate that being one of only two stills photographers inside the operating theatre, we should clear 15,000 rand.”

“Mmmm,” he beamed. “That certainly will help our research.”

And thus it came to pass, in the dead of night, that we hatched our plot. It turned out Dr. Mibashan had, or had access to, a Minox 16 m.m. spy camera. Using your thumbs to secure it behind clasped hands - fingers parting before the lens - you took your pictures and advanced the film by simply pulling the left and right halves of the camera apart a fraction, and then sliding them back again.

No one, not even Barnard himself, knew when the operation was to take place. It depended on a dead donor with a healthy heart, and they don’t come two a penny. So I parked my van outside the main entrance to the hospital and kept a round-the-clock vigil, alternating with Brian Astbury, the photographer I shared a studio with. (In the 1970's Brian founded and ran South Africa's first non-racial theatre/arts venue, The Space. Later, he relocated to London, where he taught at three of the top British drama schools - LAMDA for eight years, Mountview, where he was Head of Acting, Directing and Musical Theatre Courses, and E15, where he founded a new course - the Contemporary Theatre Course, which teaches actors how to survive by creating their own work, forming companies, etc.

The plan was that I would wait on the stairs outside the operating theatre when the big day arrived. Dr. Mibashan would leave the theatre the moment he had photographs of the operation in progress, I would hand the undeveloped film to Kenneth Wannenberg, our darkroom assistant, who would break all records to get from Groote Schuur to our city centre studio, where Brian would develop it. An hour or so later, the sequence was to be repeated. Such was the best laid plan of mice and men…

The tension built up and up as us slavering sharks circled about, waiting for the feeding frenzy to begin. A situation like that creates its own dynamic and men who are normally sane start doing the strangest things. One photographer was ordered to come down from his perch on top of a lamp post. Another was arrested while pushing a trolley back and forth outside the theatre, dressed as a nurse. Under his uniform they found three cameras.

I kept in constant touch with Dr. Mibashan and finally, with the force of a monsoon breaking, the big day was upon us. Through the years my work has put me in situations of extreme danger and high pressure. Yet I doubt if I have ever been as nervous as I was on that day. It’s the waiting, that's what does it. Every one of us newsmen, down to the last man and boy, was ready to cut the feet from under any competitor. We would kill for that world scoop. With your eye to a camera’s viewfinder, you are instantly in another world, with other laws. Lord God Scoop is the highest deity, and we all worshipped Him. Crimes committed in His name are crimes no more, but paving stones on the path to prizes.

I heard footsteps, and lurched for the broom cupboard door… As it turned out, the cupboard was locked. Just as well. Imagine what would have happened if the cleaner had found me inside! I whistled soundlessly through clenched jaws as he inserted a key, selected a broom, and locked up again. He gave me a nod and was off.

An eternity, lasting only 40 minutes according to my lying watch, came to an end when Dr. Mibashan materialised. He was ashen-faced.

“What’s the matter?” I asked, for most certainly things were not kosher.

“I was seen,” he said in a hushed, strained voice, wringing a tiny film canister in his hands.

“Seen? Seen? What do you mean?”

“Jannie Louw, Professor of Surgery. He saw me taking pictures. This is awful.”

“What does it mean? What- What do you want to do?”

And here, dear reader, is where I parted company from the really top news hounds of this world. I lacked the killer instinct. Had I possessed it, I would have inveigled the stunned Dr. M into handing over the film and before the operation was past its halfway mark, the first pictures would have arrived in London and thence further afield. And a struggling, impecunious young father would have been able to pay the rent.

From my dealings with him up till then, I had the impression Mibashan was a vulnerable man, a touch shaky. Standing there on the stairs, I felt a heavy responsibility descending on my shoulders: I had to keep this older man from being harmed, by others - or by himself.

“Maybe we- I don’t know. This could cost me my position,” he said tersely. And he was head of a whole department at the University of Cape Town Medical School, not just some minion.

“Or perhaps I can have a word with Professor Louw. Or Barnard. Maybe they’ll give permission.”

“Yes, maybe they will," I said. "After all, what does one photographer more or less matter?”

“There aren’t any others-”

“What! But surely-”

“Not a single one. I was the only person in there with a camera. Beside the transplant team, no one else has been allowed in.”

Now I fully understood the enormity of Dr. Mibashan’s distress. And what of my quandary? That tiny film canister in his wringing hands had just increased tenfold in value. We were rich beyond our wildest dreams.

Avaricious thoughts propelled me into groping for a way out.

“Look, why don’t we develop that film, see if there’s anything worthwhile on it. Meanwhile you go have a word with Professor Louw. I’ll hold sending the pictures till you give me the all-clear.”

I guess he could see the non-killer in me, for he trusted me. Which did not mean I was through with wheedling, not while baby needed shoes. The film was duly developed, the enlarger head was hoisted all the way to the ceiling, and the printing paper was placed on the floor. Even at that distance, the tiny negatives yielded only 6 by 4 inch prints. The four best pictures were blow-dried and ready for transmission. A five-minute dash to the central post office. Then a seven minute wait while a drum revolved 400 times as gradients of grey were transmitted by landline, and the first picture would emerge in London to announce our mega scoop.

"What memories that brought back," Brian emailed me when we again made contact in 2017, he from Britain and me from The Netherlands where I now live. The apartheid government had banned my photo books on femininity and lovemaking, "Gentlewoman" and "Touch Love" and I left in the eighties to find new pastures. www.magicmirror.nl/newfiles/shenanigans-6.html.

"What an extraordinary period of our lives," Brian wrote. "I remember vividly standing in the pitch-dark darkroom (we didn't have a developing tank for the Minox film) with Ken outside with the timer. I vaguely remember that I had to develop the teeny film holding it in my fingers at each end like a little flat snail. The darkroom was like a sauna and the temperature of the developer was close to 80 deg F. I didn't know how much to adjust the developing time - all guesswork. Then me standing on top of something (did we have a ladder?) in order to be able to focus the swaying enlarger up at the ceiling, while Ken had his nose to the floor, trying to see whether the dim image was in focus. A miracle we got the prints at all."

While the prints were being made, I waited in highly-strung suspended animation for Dr. Mibashan to re-emerge from the theatre. It was nearly an hour before he reappeared. He was even more distressed this time. Exactly what had transpired I did not know, but I had an image of a schoolboy who had been summoned to appear in the headmaster’s study the following day for a severe caning. The result was, Dr. Mibashan wanted us to hold fire till he could clear the matter.

Awful things were happening in the pit of my stomach. The submarine’s hatch had been closed with me still on deck, and she was about to make an emergency dive. Since age 16, when I had first earned money as a schoolboy reporter on the Pretoria News, I had sustained myself with dreams of a national scoop, never daring to hope for an international one, yet here it was... and slipping from me.

I also could not get my head around the fact that Barnard had not arranged for at least one television crew and one stills man to record the operation. There had been time enough to deal with all the disinfection protocol. Okay, leave out the TV crew, maybe that was too much. But the stills man, his friend. What the hell had become of him? Had he chickened out?

It’s true, there were rumours afterwards. Of him losing his nerve. And then, when he got wind of our scoop, he applied for a court injunction preventing me from sending the pictures out of the country. Oh bitter irony! What point was there in him trying to shoot us down when we were careening in a kamikaze dive?

What ensued was an excruciatingly slow bleeding to death of our project. Not the least of players in this tragedy was Ego. Dr. Mibashan reported that while an effective embargo had been slapped on the dissemination of our pictures, Barnard did ask him if he might use them in his forthcoming book.

To give you some idea of just how highly prized those pictures were, even three months after the event we were approached for the last time by Mondadori Press, the giant media chain in Catholic Italy, with the sum of 120,000 rand being bandied about. (What would that not be worth today!) And still, Dr. Mibashan, fearing to lose everything he had built up, would not... could not... release the pictures.

Brian remembers: "The lady from Mondadori was there on the night after the transplant. I will never forget the look on her face as us two 'yokels' said that we couldn't sell her the pictures because we had given our word to Dr. M. It was the beginning of the end for me. I was never meant to be a hard-bitten journalist with no moral compass."

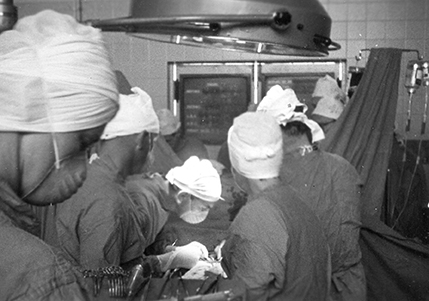

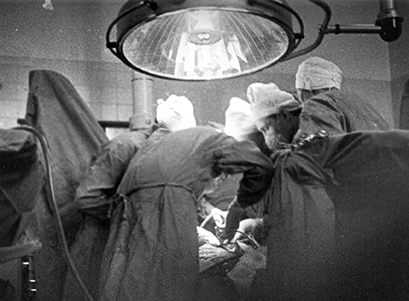

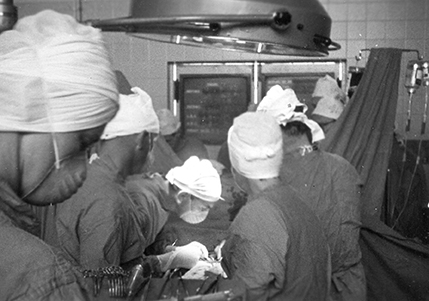

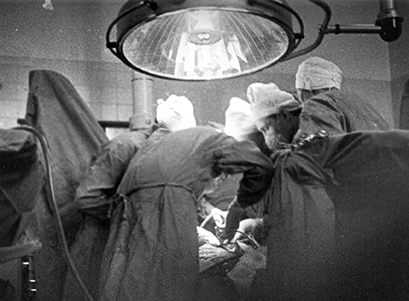

Well, I’ll spare you the details of the slow demise. Let it suffice to say that those historical photos were never, to my knowledge, published until now, here, and in Styan's book. I honestly do not remember what happened to the negatives. Maybe we gave them back to Dr. Mibashan. I hung onto that first set of prints. And don’t judge them simply as photographs. True, all you see is Barnard and his team stooped over an operating table, but transport yourself 50 years back in time when one man had the guts and gumption to take that leap into the unknown. By the “mere” replacement of a pump, he not only revolutionised heart surgery, he also brought about a shift in the way mankind looks at itself and at religion. It was, indeed, a quantum leap. And these are the only photographs that recorded the beginnings of that epoch.

Many of the major players are dead now. Chris Barnard retired from surgery in 1983 due to arthritis. He died on Cyprus on September 2, 2001, aged 78. Dr. Norman Shumway, regarded by many as the father of heart transplant surgery for preparing the ground, performed the first successful transplant in the United States on 56-year-old Mike Kasperak, on January 6, 1968, one month after Barnard’s first transplant. Kasperak lived for only 14 days more. Shumway lived to the age of 83, dying on February 10, 2006.

And what of Dr. Mibashan? Taken to South Africa as an infant from his birthplace, Jerusalem, he qualified as a doctor in Cape Town in 1949, winning the university gold medal and scholarship for the most distinguished medical graduate of his year. Some time after those first transplants, he left Cape Town. He held research fellowships in London and Salt Lake City, then settled in the United Kingdom, holding senior posts in the departments of haematology at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School and King’s College School of Medicine. He died on January 20, 2001. He was a talented violinist. And an accomplished photographer to boot. It is due to him that we have this historic record.

THE END